A conversation with Alan Klement, author of When Coffee and Kale Compete.

This is part of my series on thought leaders in the innovation space. Check out the other articles here.

Alan Klement is a researcher and entrepreneur who has successfully applied the Jobs to be Done (JTBD) theory in his own business and now works with other companies to do the same.

“I got into JTBD after an experience I had as a product manager. I did everything that I thought a Product Manager was supposed to do. I released a new version of the software product. It took us a year of development and our customers were very happy, but revenue did not go up. I’d spent half a million euros of my boss’s money to improve the product but did not move the revenue needle. So that’s when I realized I needed a different way to think about building products.”

Customers don’t have needs

Alan’s experience as Product Manager highlights a common belief in product development that all one has to do to build a successful product is uncover your customer’s needs and build a solution to meet those needs. But Alan believes this idea takes for granted that customers have needs and that they know what they want. “The concept of a ‘need’ is that of a necessity precondition. A combustion car needs gas to run. A fish needs water to breathe.”

Alan believes that when it comes to product and services consumers don’t really need anything. “We can prove this because people make tradeoffs all the time. Do I need a shower or the ability to clean myself while I stay at a hotel? Well, maybe you’re offering me a free trip to Mt. Everest, and along the way, there’s only one hotel that doesn’t have any bath. In that case, I’d be willing to give up that ‘need.’”

While it may be true that customers know what they want, Alan points out that those desires can also change over time. “There’s this concept in game theory and economics called ‘perfect information.’ In such a system, there’s nothing for anyone to learn, because they know everything. But that isn’t the case with humans. We only know what we’ve experienced or learned in the past, and we use that to project into the future. As we learn and experience new things, our opinions change.”

To illustrate, Alan offers the example of the Blackberry. “Blackberry owners assumed that they needed a keyboard to type with. When they saw the iPhone, they utterly rejected the idea of a digital keyboard. They saw it as a step backward. However, when they actually tried it — and used the rest of the phone — they thought the digital keyboard was just as good. Or even if they thought it wasn’t as good, because the iPhone was great in other ways, they were willing to give up a better keyboard for, say, access to apps.”

“It’s almost a Neanderthal way of thinking about building products. Instead of just going and jumping into what you believe customer needs might be, let’s step back and understand that relationship between demand and supply within a market.”

In the JTBD theory, Alan saw the wisdom in studying why people buy products and what they consider to be competition for the products they use. “Through studying how people think about products you deduce what we call Jobs To Be Done, or the positive change that people are trying to make in their lives as a result of building some product, using some product, or consuming some product.”

As he points out in his article Progress: The Core of Jobs to be Done, Alan views JTBD as a better alternative to the notion of customer needs because it embraces progress. “As you make progress, new desires arise and new constraints arise. When you study progress and think about the desired change that people want, you realize what they want changes. And what’s preventing them from achieving what they want can change. Instead of just this idea of a list of needs, it’s about what inhibits progress.”

In placing a singular focus on the need itself, the customer needs approach misses the context of the customer experience — what they’re going through, why they’re going through it, and what their motivation is.

“…the need is when I have a desire and there’s a constraint blocking me from achieving that desire.”

Instead, effective solutions can focus on the constraints preventing customers from achieving their desires, or as Everett Rogers describes it, the gap that exists when a person’s actuality doesn’t match their desired capability. “If you take customer need within the context of progress, I would say that the need is when I have a desire and there’s a constraint blocking me from achieving that desire. I need something to overcome that constraint and realize that desire.”

FREE DOWNLOAD

Get Our Find Your Alignment

Determine how your idea can be shifted or re-positioned to connect with and support business objectives.

Demand Profile

To visualize JTBD, Alan uses a tool of his own creation called a Demand Profile. When building the Demand Profile, Alan focuses on the desires, constraints, catalysts, and supply in the context of a customer’s experience. “The job that they’re trying to get done, is a combination of desires and a combination of constraints. The catalysts are the things that accelerate the demand by making the desires more important to me or the constraints worse to me. Then, we have the supply items. Those are things that I could consider to hire to help overcome the constraint and realize the desire.”

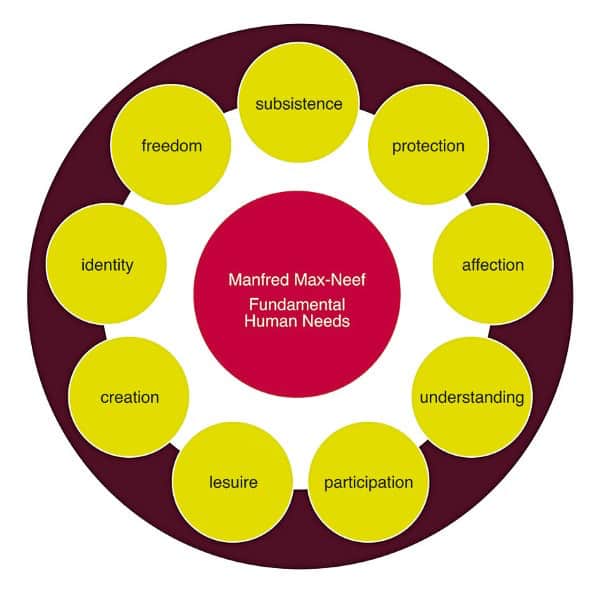

In creating the Demand Profile, Alan incorporated research from psychologists and economists like Manfred Max Neef who focus on the qualities that motivate people to take actions as the basis for describing the job to be done. He categorizes the JTBD based on Manfred Max Neef’s fundamental human needs matrix.

A theory, not a method

Rather than a silver bullet in innovation, Jobs to be Done is a theory. “It’s about explaining why people are buying products and it helps you define markets. So if you want to get started, start there. Appreciate that it’s a theory. It’s telling you how to think about supply and demand and that it’s an investigation of supply and demand and how that works within a market.”

While the JTBD theory resonates with a lot of innovators, it’s not always easy to apply in practice. “I think it goes back to the classic Western style of management. MBAs are basically cranked out. Everyone’s taught methods. And so they think in terms of everything as methods. And so when they hear Jobs To Be Done, they assume it’s a method. Something you do. It’s actually a theory about markets, demand generation, relationships between supply and demand, and why people are buying things. And that knowledge together is what should inform marketing and sales.”

Multiple strategies for growth in innovation

In addition to a blinding focus on customer needs, Alan believes that innovation can go astray when organizations fail to recognize that there are different strategies for growth in innovation. “There just seems to be this belief that if we improve the usability of our product or if we make the product better, more people will buy it. That’s just some assumption. There’s no theory behind that. There’s not really thought put into whether that is true or not.”

Alan sees three different approaches to innovation. One approach involves making adjustments or adding features to a product to capture customers with specific needs who are interested but forced to look elsewhere. “But you need to have a plan to go out into the market and find out why people are not buying your product, and then change it specifically to capture that group of people.”

Products can also be changed to entice existing customers to buy more of it. “An hour ago, I upgraded my Google G-Suite from the Basic to the Enterprise version. And I did that because I wanted to record my Google Meets. So that’s a way that Google is extracting more revenue from me. They’re offering add-ons or they’re offering me things that an existing consumer will pay more for.”

The third option is to create something entirely new to bring in new customers, sell to your existing customers, or both. “I think that those three different strategies for increasing your revenue all require a different research process and a different design process.”

You can’t measure innovation

According to Alan, innovation isn’t something that can be measured. “It’s a concept. Just like love or friendship. You can’t measure concepts — or anything else that lives in our heads.”

“I don’t understand why you’d want to measure innovation.”

Measurement belongs in the realm of observable phenomena and physical things. “I don’t understand why you’d want to measure innovation. Who cares about that? In a free-market economy, the only thing a private company cares about is revenue. Because without it, it wouldn’t exist. I suppose you could say revenue is a ‘need.’”

“Numbers only tell you the effects of the system, but don’t tell you anything about the system itself.”

The emphasis on measurement in innovation is something Alan believes speaks to a problem with how we approach business management in the West. “Part of the problem with a lot of Western styles of management is they want to look at numbers. And they think numbers tell them things, tell them facts. If there’s no number, then I can’t make a decision on something. But that’s a fault in management because you can make up a number for anything. Numbers only tell you the effects of the system, but don’t tell you anything about the system itself.”

Start with supply and demand

More important than measurement is that innovation programs begin with a strong understanding of the market. “First off, I believe it starts with understanding existing markets — what supply and demand looks like today. What are consumers buying and why are they buying it? Because even if you are trying to advance the market, change the market, you still have to know where you are so you can begin changing it.”

The next step is implementing a process around imagining how things could be in the future. “If I were at a company, I would pull in people who were excited about designing new things for the organization, who had different experiences — people from marketing and sales background or people from a product or engineering, customer support. Bring these people together because they’re going to have different experiences of interacting with consumers and market behaviors that they can bring to the process. That helps you imagine how the system could be in the future.”

The final piece is establishing a process to experiment, learn, and test hypotheses. “Start testing with consumers and see if it gets them excited. See if it gets them wanting to change how they do things now to adopt our view of the future.”

Alan believes forming innovation programs should start with someone in a position of authority who believes there’s a revenue opportunity. “Some ultimate decision maker should pull together a team that can focus on discovering and flushing out this opportunity and thinking about solutions or things that can sell to fit into this opportunity.”

From a tactical perspective, team formation based on the principles of group dynamics involves multiple small, cross-functional groups. “You don’t want to have 20 people in a room. I don’t know how you would manage that. Two people or one person might not be enough to bounce off ideas. So it’s whatever produces a good mix of intimate setting, but also different people with different backgrounds who can comment and challenge ideas.”

Each team develops product ideas separately and then all teams come together to share their ideas. “That way you get the focus and quickness off a small team, while also getting the shared, collective knowledge of a large group of people.”

Once a solution is determined, Alan believes that sharing with the larger organization is most powerful for achieving buy-in when teams share the story of how the solution came to fruition. “This is straightforward research sharing. Here was our objective. We believed that there was a growth opportunity, revenue opportunity in this area. Here’s how we went out and did the research. Here is the data. Here are the concepts that we created based upon those data. We tested those concepts. Here were the results. And therefore, we are choosing concept C because that was the one that people responded most favorably to and expressed a willingness to pay for, more than anything else.”

A flaw in the theory of disruption

The story of the iPhone is a favorite innovation success of Alan’s for its unconventional approach to innovation. “They did everything right by going against, even today, all of the beliefs of how innovation should be done. Again, they didn’t go out and study customer needs.”

Steve Jobs looked at the existing market of smartphones and thought taking up half of the screen real estate with a keyboard ruined the customer experience. “Blackberry owners thought no keyboard, no way. Go back and just read all the pundits. But actually, Apple became the most successful company of all time with the most successful product of all time. And Nokia went bankrupt.”

Alan views the iPhone as a prime example of the flaw in Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruption. “If you go back and look at Clay’s research, he’s doing everything by product category. He said PCs disrupted mainframes. That’s completely wrong. PCs and mainframes never competed. Actually, mainframes are still alive and well today.”

Due to his focus on the product category, Christensen saw the iPhone as a premium smartphone. “But he didn’t recognize, actually, it’s an alternative to a TV, to my laptop, to reading a newspaper, to staring at the wall while I’m at the doctor’s office or the magazines in the doctor’s office. I mean, that’s what it competes with.”

Alan views product categories as more of an indicator or lens through which to view innovation.“Maybe when you think about introducing a new supply option for some demand, you instead consider if this new supply is going to make product categories obsolete.”

Even Clayton Christensen himself seems to have abandoned the notion of innovating within product categories. “Clay wrote The Innovator’s Dilemma. It was a huge success. And then, of course, he’s like, I have to do a follow-up. I discussed a problem. I should probably offer some solution to that problem.”

That solution materialized after he met Rick Pedi and Bob Moesta. When Christensen heard the idea of Jobs to be Done, he thought it might be the answer to The Innovator’s Dilemma. “It was the idea of not focusing on a product category, but focusing on what the product does for the person. Snickers is not a candy bar. It’s not about the chocolate and peanuts. It’s about satisfying my hunger on the go. And he felt that phrasing, that re-contextualization of markets, was what would solve the innovator’s dilemma.”

The story of the iPhone is a perfect example of why Alan doesn’t ascribe to the customer needs approach. “Supply is not created to fit demand. Supply actually creates demand. So don’t think that demand is something out there, that you create something to fit that demand. No, if it’s really something new, you introduce something into the market, and that creates demand for it. Because there has to be something out there. In order for me to want something, it has to exist.”

Simulated shopping

Alan’s advice for studying the market when a product is entirely new uses an approach he calls simulated shopping through which he tries to uncover if people will want a new product and, more importantly, if they’ll be willing to pay for it.

“In an interview with someone, we try to recreate how they would shop. One way that we do it is we create fake Amazon pages for the product that doesn’t exist yet. Then we show this to the person in an interview or through Zoom and watch them browsing.” Talking through their decision making process and learning what product the interviewee would ultimately buy is a low-risk approach to finding a revenue opportunity for a new market solution that can help predict whether or not it will sell before the costly work of building the solution occurs.

For more information on Jobs to be Done and how other entrepreneurs have applied it to create successful products, check out Alan’s book When Coffee and Kale Compete.

If you want to read my other articles about innovation experts and practitioners, please check them all out here.